Objects, Instances, and State in Distributed Systems

When we model data structures and encode business logic into our applications, we generally use either a functional programming model or an object-oriented one. In a single process, this choice can be a matter of personal preference, but in distributed systems this choice can actually have significant impact.

The functional versus object-oriented wars have been raging since the dawn of time, with no clear victor in sight. The waves surge in one direction and then recede, catching impressionable programmers in the riptide. This blog post isn't about which one of these models is better. In fact, neither of them is objectively better. This blog post is about how these paradigms are represented and perform in distributed systems.

Let's say we're going to model the distributed back-end for an online game. It's a fantasy game and we've got team after team working on all of the various bits. To keep things simple, we're not going to use an existing backend or an ECS, we'll roll it ourselves.

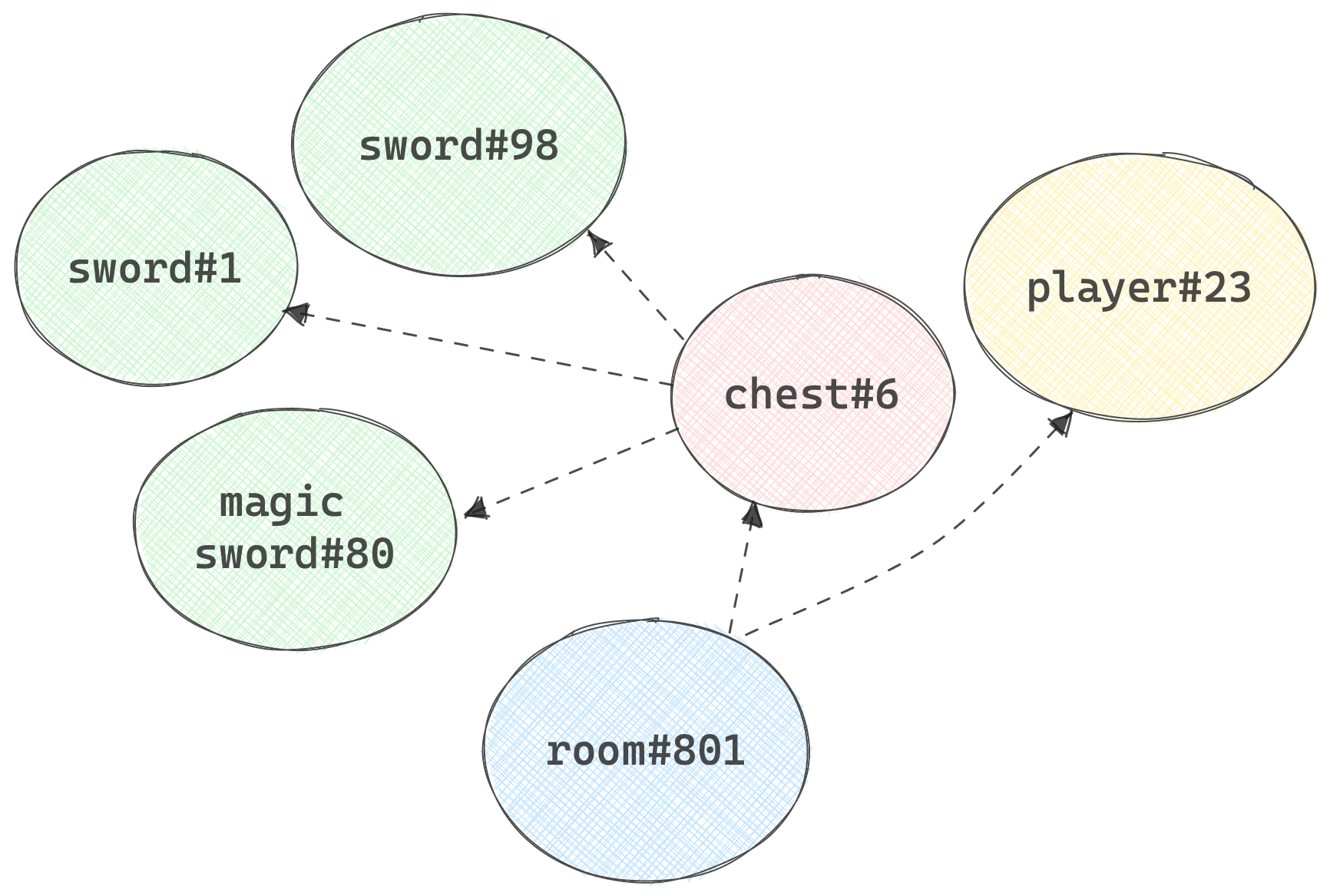

To start, let's examine the object-oriented approach. In this paradigm, every "thing" in the game is represented by an instance of an object. We'll have an instance of a room, and in that is an instance of a chest. Inside the chest we might have two different instances of sword (one might be slightly damaged), and an instance of magic_sword.

To mutate the state of one of these things, we call associated methods:

sword = new Sword();

sword->set_condition(12);

chest->add(sword);When everything is in a single monolithic process, we don't have to worry too much about the consequences of writing code like this. But now let's imagine this is a massively distributed backend. The sword, chest, room, and player instances could all theoretically be in different processes or even on different nodes.

When we want to make a function call on an instance, say magicsword#80, we need to locate that instance (because there's only one of them) in the cluster and call the function on it, which desugars into a request/reply message send.

Systems like Akka do an amazing job of optimizing this pattern. Smart hashes make locating an instance on a node a fixed cost operation. Message sending can take place over any number of high-speed and durable transports. You can also bolt on things like event sourcing, durable state management: whatever your heart desires.

One of the things we need to keep an eye out for in this model are "hot objects". Let's say in this game we've got a room called mystical_plaza. When the game boots up, we get mystical_plaza#1, and it is homed to just one node in the cluster. Now someone throws a party in this plaza and invites 1,000 of their closest friends. Now we're pushing thousands of messages per second all through this single instance of a plaza. We could have 30 nodes in the cluster, but because all of the people in our system are crowded into just one plaza, 29 of those nodes are underutilized.

You've probably seen this happen if you play a lot of online games or MMOs. Instance 1 of the mystical plaza reaches capacity and so now we need to spin up a second instance on a new node. This is often called a shard. Now we have two mystical plazas, each with completely isolated crowds (cross-world chat is a topic for a different blog).

So how does this behavior change when we don't model the world as objects and instances, and we instead take a more functional approach? Instead of having an object for the mystical plaza and invoking a bunch of mutating functions, we might instead have a module called mystical-plaza. In this module there are functions like handle-enter and handle-exit or init or handle-emote etc. Each of these functions can then take, as an argument, whatever state is relevant for the room at the time.

When we model in OOP, methods like sword->wield(player) can "un-objectify" into functions like wield(sword, player). So it's entirely natural to assume that wield(sword, player) is pretty much the same thing as calling a function in an FP environment. In a single monolith, it is actually quite similar.

When we distribute functions across a cluster, however, the default behavior is a little different. On each node in the cluster, we could have the code for the function plaza-hello, but there's no internal state. This means that, as players file into the plaza, each one could invoke the "closest" plaza-hello function and the runtime would be responsible for passing the state into that function. The default mode is one where "state has no home", and so it might be easier to balance out the utilization of the system.

When distributing functions, we often (there are exceptions, as always) don't need to shard and segment because we don't have one room running on one node, we have the same code running on all the nodes, being invoked as frequently as needed by the sum total of consumers.

Erlang/OTP is one example of distributing functions. You can think of an OTP process like a "frozen function", where the function is "paused" along with the parameters that invoked it. They consume next to zero resources while not being used, so we can have millions of them at a time.

I'm not saying that one approach is more scalable than the other. I'm saying that they have different scale modes. When we distribute object instances, we either need to shard them or figure out a decent replication system to ensure that "hot instances" can be spread out. Akka can actually do that for you, too. When we distribute "freezable functions", it might be easier to spread them out across a vast cluster, but in many cases developers find these systems more difficult to reason about.

So, what does all this have to do with wasmCloud? Using wasmCloud means you don't have to be locked into one paradigm. Even better, you can choose one paradigm when you start out and then turn knobs and make runtime adjustments to lean in either scale mode direction.

If you want to run everything like a bunch of ad-hoc activated functions that never maintain their own state and just take arguments, then you can absolutely do that. Actor components that handle calls can be scaled vertically on each node and horizontally across the cluster.

If you want to run your actors with state associated with each one, you can do that as well, but you can also have the modules with that code scaled out as much as you need, and state delivered to the actor when needed. Combining the power of WebAssembly components, the wasmCloud lattice clustering technology, and flexible and extensible capability providers (which can provide state) means you don't have to pick a paradigm and be stuck with it forever. You can get the best of both worlds, and have a solution that leverages the best ideas from both Akka and Erlang/OTP.

You can pick one, or both, and adjust over time as your application, customer base, and capacity needs evolve.

Take a look at our getting started guide and decide for yourself what kind of paradigm you want to use to build your next amazing distributed application.